One of the criticisms often levelled at the Catholic Church is that we do not read enough of the Bible. The length of today’s Gospel might suggest otherwise, and this was the shortened account!

[For the reader: A reference to the passage used is given at the end of this text.]

The criticism is not entirely unfair however, and while we will never embrace the sola Scriptura, Scripture alone approach of Protestantism, it is a fair question to ask – when and how do we read and reflect on the Word of God?

One approach is Lectio Divina, a process in which a piece of Scripture is read three times, with a period of reflection between each. It is all very contemplative, allowing a word or phrase to jump out at us; that is the word or phrase which we are then called to consider the importance of, for ourselves and in our lives.

Each person brings their own personality to this sort of reflection, and I find that my curious nature is often drawn to the little details: Why did the writer choose to include that – what is the importance of an often apparently trivial detail. When I was reflecting on today’s Gospel, my attention was drawn to a couple of things:

John’s Gospel wasn’t written by him personally, but by a community of his followers. Those followers would have memorised his stories and teachings word for word, after the Rabbinic traditions of the time; but why did John insist that they remembered that this meeting happened at the sixth hour, or include the snippet that “Jews, in fact, do not associate with Samaritans?”

It is no secret that the Samaritans had a long history of conflict with the Jews. They were the remnant of the Northern Kingdom of Israel, with the Jews being the remains of the Southern Kingdom. They had freely intermarried with non-Israelites, and as we hear alluded to in the Gospel, they worshipped God at this mountain, called Gerizim, rather than at Mount Zion – the Temple Mount of Jerusalem. Worse still, the Samaritans had opposed the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem after the Babylonian exile, and the Jews had destroyed the Samaritans’ Temple in turn. It’s safe to say that while the Jews looked down on the Gentiles – the non-Jews, they openly hated the Samaritans.

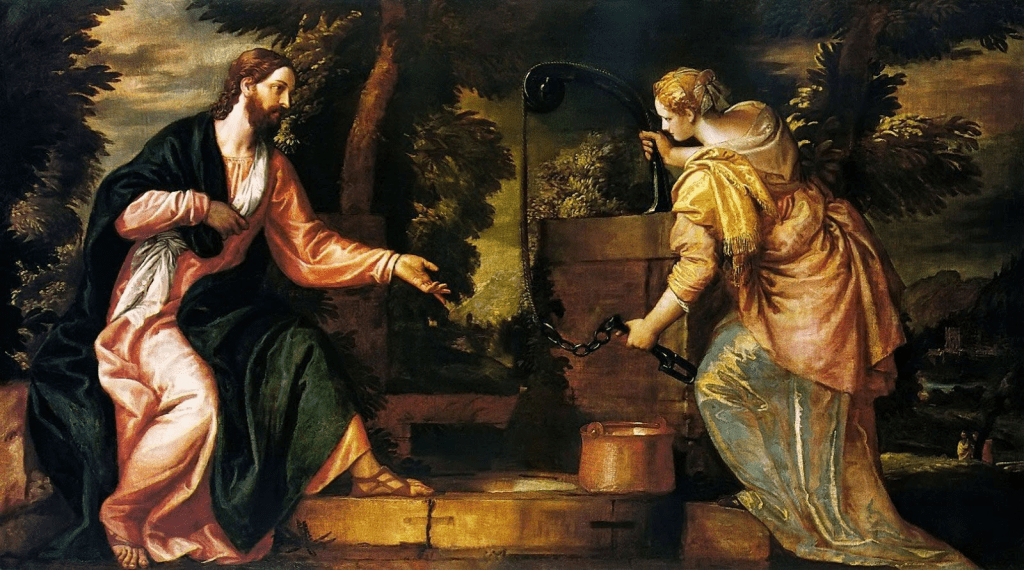

And what of this sentence “it was about the sixth hour?” The daytime was divided into twelve hours, so the sixth hour refers to the middle of the day, the hottest part of the day; and here was this woman alone at the well. Water would have been collected by the women in the early morning, when the day was cooler and the walk back to the city less arduous. So what was she doing there in all that heat?

Another thing that often catches my eye with the readings at Mass is when I look at the reference at the top of the reading and there are verses missing. In this shortened version, what was said in verses 16-18, and 27-38? The first of those gaps is significant here – Jesus tells this woman something about herself that he should have had no way of knowing – that she had had five husbands, and was now with another man who was not her husband. This is why she calls him a prophet, and later says “he told me all that I have ever done.” It is also very likely the reason that she was disliked by the other women of the city, so much so that she had to come to the well alone at the sixth hour – in the heat of the midday sun.

This all adds up to a woman who was as despised as it is possible to be – excluded by her own people, and they themselves a people who had been shunned for centuries by Jews; Jews like Jesus.

And yet the Lord offers her, even her, living water and eternal life. There is hope for all of us, I think.

But she doesn’t just take from the Lord; she passes on what she has received. Think of those you consider to be credible sources of information – are any of them outcasts like this woman? I suspect probably not. Yet the zeal with which she spoke of the Lord when she returned home inspired those in the city to welcome him and to believe.

That same living water, that same eternal life, is offered freely to every human soul, to every one of us. All we have to do this Lent is turn to him, worship him in spirit and in truth, and he will grant us everything that he promised to the woman at the well; and what is more, we will be filled with the same intensity that caused her, an outcast of outcasts, to speak so fervently, and with such conviction, of the Good News of God.

Gospel Passage for the 3rd Sunday of Lent, Year A, Shorter Form: John 4:5-16, 19-26, 39-42