One of my many obscure interests is in the rhythm and stress patterns in texts, especially in poems and liturgical texts such as hymns, psalms and prayers. Over the past few years one particular stress pattern used when praying the Our Father has intrigued me because when it is combined with the accents of the Midlands of England, it suggests that an important aspect of the Our Father is being missed or misunderstood. If you have a different accent, the pronunciation part of my thoughts below may not mean a great deal, but I hope that the ideas of stress patterns will.

All of this may seem a strange starting point for a religious reflection to take, but please bear with me.

Whether we realise it or not, in spoken English we emphasise certain syllables over others. This is because every text contains stressed and unstressed syllables. When chanting, these syllables become even more important, partly for rhythm and partly because they indicate on which syllables the note will change. This is why the psalms of the Breviary are written out with accents – the accents indicate the syllables to be stressed as one reads or chants. Consider the opening of Psalm 50 (51):

Have mércy on me, Gód, in your kíndness. *

In your compássion blot óut my offénce.

O wásh me more and móre from my gúilt *

and cléanse me fróm my sín.

Below is a recording of this verse being spoken aloud:

And sung to psalm tone 3g, as found in the Liber Usualis:

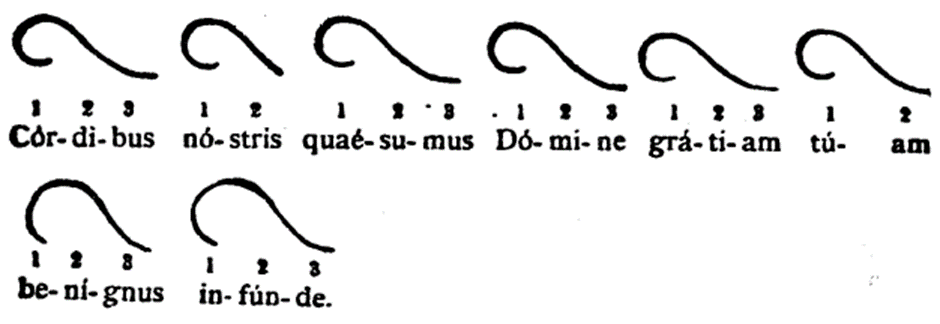

The Liber also contains (in Latin) a simple, yet wonderful illustration of this ebb and flow between stressed and unstressed syllables:

This brings me neatly to the title of this reflection. The word us can be read in two different ways in some English accents. In the Midlands of England, it is often pronounced uzz, with a long ‘z’ sound, rhyming with buzz. Sometimes however it is pronounced uss with a shorter, harder ‘s’ sound, rhyming with fuss; this is less common and usually happens when the word us is itself a stressed syllable, such as at the end of a phrase or sentence.

This may all seem terribly trivial, but consider now the final sentence of the Our Father, punctuated and line-broken as it appears in the Missal:

“Give us this day our daily bread,

and forgive us our trespasses,

as we forgive those who trespass against us;

and lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil.”

The Our Father is of course a prayer we say regularly, and it can be very tempting to rattle through such prayers without really considering their words. Although one sentence, the semi-colon at the end of the third line is a clear split between two separate requests: we ask for God’s forgiveness in lines two and three, and then ask him to keep us clear of temptation and sin in the future. As line three ends a phrase and a specific request we should make an effort to pronounce us with a clear, short uss sound; but in haste we are often looking straight to the end of the sentence and resort to the longer and more common uzz sound instead.

On a deeper level, when we are hurrying, we are not fully considering the words we are saying; we don’t take the time to appreciate the ‘us’ in those lines. We are asking God’s forgiveness for the things we do to offend him, but only in the same manner as we forgive those who sin against us. That is a big deal for the Christian life – we are called to forgive as we wish the Father to forgive us. I don’t know about you, dear reader, but I have a great deal I would like forgiveness for; and so I must endeavour to be forgiving in every single situation where someone upsets or hurts me.

Of course, we are not trying to strike a divine bargain with God – he will, in his love, forgive us anything anyway, as long as we show true repentance. But Jesus did not leave us these words in example for nothing; he left them as a guide both for prayer, but also for life. We will live a better, a more fulfilled, and, most importantly, a more holy life if we follow the example of forgiving others who trespass against us.

That is the message which we gloss over and do not take the time to consider every time we rush through an Our Father, all because of a lack of emphasis on a word just two letters long.