It is often pointed out that the character of St Joseph never speaks in the Gospels. His earthly fatherhood is one of silent constancy. Without the words themselves we still see a man of faith, who trusted in the messages given to him by God; and in that faith he was able to love the Lord. There is a great deal of good in his silent example alone, but this Epiphany a connection occurred in my mind between St Joseph and the lesson of the Magi. Credit must go to my school’s chaplain for prompting this connection in something he referred to in his Epiphany homily, 2023.

The Magi’s journey would not have been easy for many reasons: the distance; the weather; the dangers of robbery and so on. One of the difficulties not often considered would be language. The Magi were educated men, and when they came searching for the infant King of the Jews they logically went first to Jerusalem. There they conversed with the great and the good; learned scholars who had spent their lives in the study of various disciplines, and of course, King Herod himself. Aramaic was not a widely known language, so it is likely that these conversations took place in a common language such as Hebrew, Greek or Latin, or through court translators. The Magi would have been prepared for this; they would have known how the courts of great men worked, and the etiquette to be followed. They asked their questions and were honest in the answers they gave to Herod’s questions in return. But then they were pointed to a small town south of the city; there would be no scholars or translators there.

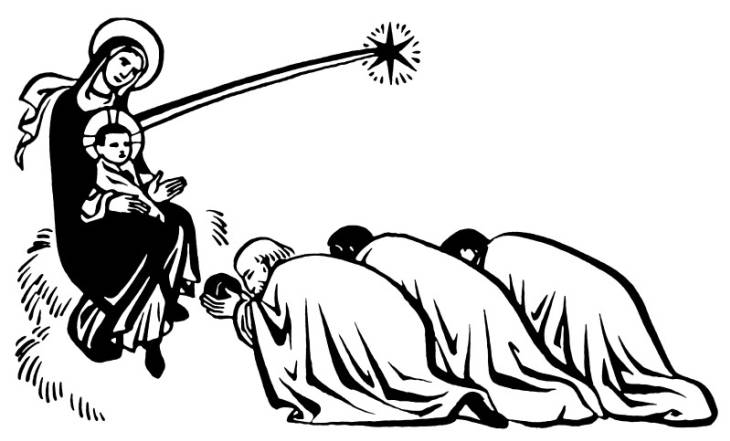

And so comes our parallel with the silence of St Joseph. The talkative Magi of Jerusalem do indeed find what they sought. “Going into the house they saw the child with his mother Mary, and falling to their knees they did him homage.” St Matthew puts no words into their mouths now. Perhaps a difficulty of language rendered conversation impossible; perhaps they were struck with a divine awe; perhaps there was an awkward and unrecorded conversation of sorts. Whatever the truth of that visit, St Matthew chooses to recount their visit as an example of silent homage to the Christ-child. They knew that this child was something special. Psalm 111 teaches that “the fear of the Lord is the first stage of Wisdom.” It seems from their visit to Jerusalem that their knowledge of the Jewish scriptures was lacking, but if proof of the Magi as ‘wise men’ were needed, we should have all we need in the way that they fell to their knees in silent wonder.

From the earliest days of the Church silence has been recognised as a powerful thing. The Lord himself would retreat into the wilderness alone or with his disciples to pray and commune with his Father. John the Baptist, the desert fathers and medieval hermits all recognised that the Lord could be found in the quiet of the wilderness. Contemplative religious orders spend much of their time in silence listening for the Lord’s guidance and praying for the needs of the world without distraction.

Of course for those of us in the secular world, noise is a constant. Sometimes that is external noise: cars, music and conversation around us; but sometimes it is the noise of our own minds, which cannot switch off from the cares and worries of daily life. Fortunately as Catholics we have a beautiful solution to this. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, whether at Exposition with the Lord in a monstrance or of the reposed Sacrament in a tabernacle, gives us time to remove ourselves from the noise of the world. Any church provides the respite from the external noise, but releasing our own minds is far more difficult. I do not intend to give a list of exercises for quietening one’s mind in prayer here, but I will suggest that it takes practice, and we should not be disheartened or put off because we find it difficult to let go of our earthly worries the first time, or consistently every time we try.

What we can and really must do, is make the effort. While our internal journey is very different from the travelling of the Magi, it can seem just as difficult. What we can be assured of however, is that it has the same end; to offer our true and complete homage to the one Lord and Saviour. We can be sure that whenever, and however often we come to him, the Lord will be waiting for us: “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever.”