Who is this guide for and what does it hope to do?

This guide is written for those hoping to introduce themselves, or a novice choir, to the singing of psalm tones. This may be for Mass, the Divine Office, or just for one’s own prayer life. It may sound complicated on the first read through, but hopefully with the sung examples to listen to as you go, you will be able to make sense of things. Do persevere, it very quickly becomes a natural process.

What is this guide not?

This guide is not intended to delve into Gregorian chant, its notation and the more complicated Modes of singing the psalms. We will stick to modern notation and a discussion of how to annotate lines of a psalm for chanting.

What is chant?

Firstly it should be said that chanting is not singing in the modern understanding. Singing has two fixed requirements of the singer: pitch and rhythm; Chant has pitch (though very easily changed) but rhythm is much more flexible. Think of it as a combination of speaking and singing. More on this shortly.

Why ‘tones’, not ‘tunes’?

A (hymn) tune is written for a specific number of syllables in each line. Each syllable has a note or notes attached to it. This means that they only work with the correct number of syllables.

A tone has ‘reciting notes’ which are used for most of each line, with a movement of pitch toward the end (and sometimes at the beginning). This allows it to be used for lines of different lengths, such as those of the psalms.

How are chant tones shown with modern notation?

Usually the reciting and final note are shown using the semibreve symbols, as these can apply to more than one syllable. The moving notes are shown as crotchet notes (usually without the stems.) The example we will use throughout this guide is shown below:

Many psalm tones, including the one above, are written to allow for the singing of different-length stanzas in the psalms. Older tones generally only include two lines.

How do I/my choir know when to move note?

With the text of the psalm written out, it is normal to indicate the syllable of the first moving note by changing the font (underling, emboldening, italicising, or even all three).

Let us take some examples from the responsorial psalm for the Seventh Sunday of Easter (Year A), Psalm 26(27), with the moving notes underlined, in bold and italicised. Consider the response below, which uses only the first and final lines of our tone:

I am sure I shall sée the Lord’s goodness

in the lánd of the living.

The first stanza of this psalm has four lines, so uses the first, second, third and final lines:

The Lord is my líght and my help;

whóm shall I fear?

The Lord is the stronghold of my life;

before whóm shall I shrink?

The next verse has six lines, so uses all six lines of the tone:

There is one thing I ásk of the Lord,

fór this I long,

to live in the hóuse of the Lord,

all the dáys of my life,

to savour the sweetness of the Lord,

to behold his temple.

How do I choose which syllable to move note on?

This is where it does get a little difficult. When preparing the psalms to be sung, one must decide which syllables to mark as the first moving notes. This is where the idea of thinking of chant like speech comes in: As we speak we naturally stress certain syllables, and we need to identify them.

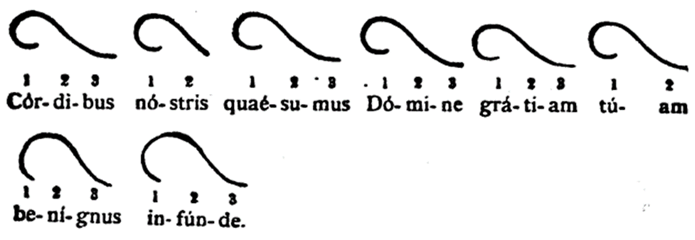

The best description I have come across this comes from a Latin resource called the Liber Usualis, which includes the following image to relate the lilting rhythm of the text, with the high-points being placed over the stressed syllable:

These stressed syllables should be marked on a text, usually with small accents above the (first) vowel of the syllable. Consider this stanza from an earlier example, accented fully:

The Lórd is my líght and my hélp;

whóm shall I féar?

The Lórd is the strónghold of my lífe;

before whóm shall I shrínk?

That is the difficult bit, the next rule is simple: The final note is reached on the final (accented) stressed syllable, so to find the first moving syllable just count backwards by the number of moving notes. All of the lines in our sample tone have two moving notes, so the moving syllable is two before the last accent on each line. Our stanza therefore becomes:

The Lórd is my líght and my hélp;

whóm shall I féar?

The Lórd is the strónghold of my lífe;

before whóm shall I shrínk?

It is worth noting here that often in English the final note is only used for a single syllable, as is the case for all four of these lines. This is because we tend to stress the last syallable of a sentence; but it is fine for the final note to be used for two or even three syllables, depending on where the last stressed syllable falls. An example of this can be seen in the last line of the six-line stanza seen earlier, with the two syllables of the word ‘temple’ being sung using the final note.

Unusual Considerations

There are three complications which must be considered, all of which generally flag themselves up on a first attempt to sing through:

Firstly, you may have noticed in the first examples above that some lines had an extra syllable underlined, always that immediately before the moving syllable. Where the final syllable of the reciting note (that is, immediately before the first moving note) is a stressed syllable, it is natural to hold the note slightly. I add a simple underlining where this is the case as it draws the eye more clearly than a tiny accent. Consider the famous opening verses of Psalm 22(23), noting the holding of the syllables Lord, green, gives, and ‘war’ in the first, third, fourth and fifth lines, respectively:

The Lórd ís my shépherd;

there is nóthing I shall wánt.

Frésh and gréen are the pástures

where he gíves me repóse.

Near réstful wáters he léads me,

to revíve my drooping spírit.

A held note can also be used when a significant punctuation mark occurs mid-line. Again, for the ease of the singer(s), it is helpful to underline that syllable.

Secondly, it is not uncommon for a verse or stanza to have an odd number of lines – three or even five. Some psalm tones are written to account for this, but most are not. The thing to do here is to break the verse or stanza up into ‘pairs’ of lines using the meaning of the text, with one ‘pair’ having the extra (and therefore three) line(s). In the ‘pair’ with three lines of text, the reciting note is held all the way through to the end of the second line; the first line (on which the note is held) is usually marked with an ‘obelus’ or ‘dagger’. Two verses of psalm 94(95) are given as an example below:

Come ín; let us bów and bend lów;

let us knéel before the Gód who made ús:

for hé is our Gód and wé †

the péople who belóng to his pásture,

the flóck that is léd by his hánd.

O that todáy you would lísten to his vóice! †

‘Hárden not your héarts as at Meríbah,

as on that dáy at Mássah in the désert

when your fáthers pút me to the tést;

when they tríed me, though they sáw my wórk.’

Thirdly, and most rarely, some lines of text are very short. Some sources would have the moving note as the first syllable (with the reciting note not being used at all.) However it is acceptable, and easier for novices, to sing more than one note on a single syllable in this case. Consider the example of the last verse used on the Seventh Sunday of Easter (Year A), which requires both moving notes to be sung on the word ‘his’ in the final line:

O Lórd, hear my vóice when I cáll;

have mércy and ánswer.

Of yóu my héart has spóken:

‘Séek his fáce.’

Conclusion

I hope this has not put any budding cantors or musical directors off. The best way to learn is to listen to some alongside the tone and listen for the different features. It does get easier and soon you’ll be able to annotate as you go on the first sing-through of a psalm (really!)

The other thing that will prove invaluable is having someone who already knows what they are doing. I hope you have someone like that to call on, but if not, you are always welcome to contact me with questions at martin@martincasey.uk.

Below, I’ll attach a Word document copy of this post, which will not have the recordings, but will include a few ready-marked psalms at the end for you to have a practice of. They get progressively more intricate as you go through them.

Download: