Audio Recording:

Text:

You may be familiar with the work of the Monty Python comedy troupe, and if you’re young enough to not be, it may be worth an hour or two on Youtube exploring what previous generations found themselves chuckling away at.

One of their most famous sketches involves a man returning a freshly bought parrot to a pet shop; as it turns out that the parrot is, to be blunt, dead. Much of the humour in that sketch comes from John Cleese’s expertly delivered litany of British euphemisms for death, in his attempt to convince the shopkeeper that the purchased parrot is, again to be blunt, most definitely dead. Some of his phrases are crudities: he’s a stiff; he’s kicked the bucket; he’s fallen off the twig. Some are socially sanitised phrases to avoid the ‘d’ word: he’s passed on; he’s no more; he’s bereft of life. Still others are much closer to a religious understanding of death: he rests in peace; he’s shuffled off this mortal coil; he’s gone to join the choir invisible.

In today’s Gospel Jesus puts words into the Father’s mouth in his parable. Words which include an ominous euphemism for the man’s death: “This night, your soul is required of you.” That would be a very dark phrase to add in to Monty Python’s list; but it gets to the heart of Jesus’ teaching in today’s Gospel. When we are called to judgement, only our soul matters.

This past week I have been in Ireland, but before I left on Monday I attended the funeral of a former colleague. There was a good number of present and former staff there, and we were sharing stories and memories, as you do. One recurring thought that kept coming up in discussion was the sadness of a man who worked all his life, paid into his pension and so on, only to develop the symptoms which ultimately killed him, within a year of retiring. I was reflecting on that sadness on my drive to the West of Ireland and it dawned on me that it shouldn’t be thought of as sad – frustrating perhaps, but not sad. It is right and sensible to provide for ourselves, in working life and ahead of our retirement; but ‘our souls being required of us’ is not something that we need to fear if our souls are ready to go. There is a difference between seeking to provide what is just and fair for ourselves, and hoarding far more than is necessary. This is the real difference between simply ‘filling our barns’ and tearing them down and building newer, unnecessarily larger ones.

This all speaks of course of greed and at the heart of greed lies envy. We live in an age of advertising; where we attach something as simple as a certain shade of a colour, a certain sequence of musical notes, or a certain slogan to particular products. All of this makes us want, desire, or in a word used in all three of today’s readings, covet (which the first reading identifies as a form of idolatry). We begin to desire these earthly things even over that which is good for our souls. That is sin in its strictest sense – it causes our souls to turn away from God. And to say it again; when we are called to judgement, only our soul matters.

Greed and envy then are things to be fought against; and as we much about in Lent, the Church gives us three spiritual weapons with which to fight sin and the temptation to sin: prayer to orient our souls always towards God, and away from the distractions of the world; fasting to discipline ourselves in small things, so that we can be sure of our ability to resist more serious temptations; and charity to align our wills more closely to that of God, who himself is Love.

The catechism speaks most of that last as the most useful weapon against greed and envy. It says that: “envy represents a form of sadness and therefore a refusal of charity; the baptized person should struggle against it by exercising good will.”

Whilst in Ireland I went on pilgrimage for the first time to Lough Derg, which if you don’t know of it is a particularly ascetic three-day programme of prayer and of fasting. It involves a great deal of what might be seen as old-school Christian practices: isolation on an island; bare feet throughout; a single meal of dry bread and black tea; an over-night vigil without sleep; and literally thousands of meditative prayers, many said kneeling on bare rock. If that sounds terrible to you I would simply say don’t knock it until you’ve tried it. Last Sunday Fr John told me, “you’ll either really enjoy Lough Derg, or you’ll really enjoy coming away from it!” It was a difficult, but massively fulfilling spiritual exercise, focussing on the first two weapons – prayer and fasting. As I drove back in the early hours this morning I was thinking where does the final weapon, charity, now fit in? What love is now going to be manifest in my life as a result? I don’t yet have an answer to that, but I will trust it to God; which brings me to my final point.

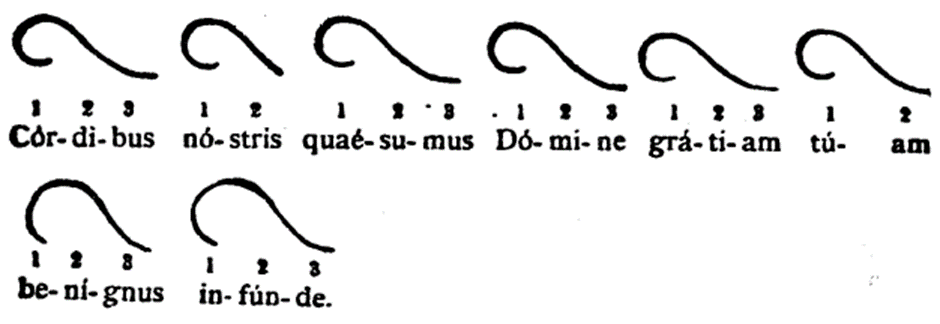

For a third time: when we are called to judgement, only our soul matters; but we are fooling ourselves if we think that we alone are in control here – like all good things, material and immaterial, the spiritual weapons of fasting, prayer and charity are rooted in, and draw their efficacy from, God’s good grace. As with all things, we must cooperate with God’s grace if they are to have value. Going without food is not fasting in a spiritual sense unless we intend the discipline to avoid sin. Saying the words of a hundred Our Fathers is not truly prayer unless we intend those words to be carried into heaven. Doing good works is not charity unless we truly intend the good of the other.

I will finish with a quote from St John Henry Newman, who it was announced last week will soon be declared a Doctor of the Church – a saint whose work has contributed points of crucial importance to Catholic theology and dogma. His point ties together the two ideas of rejecting the riches of the world and instead cooperating with God’s grace in the preservation of our souls. He wrote “Life passes, riches fly away, popularity is fickle, the senses decay, the world changes. One alone is true to us; One alone can be all things to us; One alone can supply our need.” That One, brothers and sisters, is Almighty God himself.